Dear friends,

What a wonderful day we had today. Thank you so much for making the 30th anniversary of my ordination to the priesthood a special occasion. The hats, the cake and champagne, the cards all were wonderful. It is very hard to believe that I have been doing this work for 30 years. What a blessing it has been, especially the years at St. Dunstan’s.

Some of you have asked for a copy of my sermon, which wasn’t really a sermon, but more a reflection on how I got to this point. It is attached (and it is longer than the usual sermon).

When I look at this picture I realize it really has been 30 years. I look so young! So does Joe.

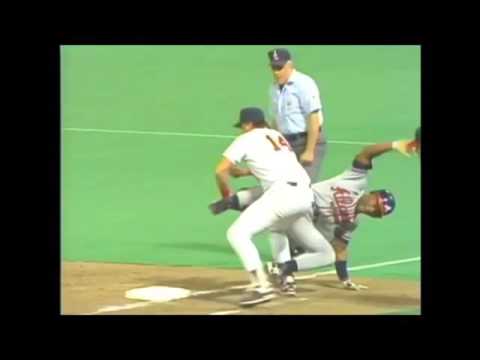

One other thing to share. I have a good friend of 40+ years, Howard Sinker. Howie has had a long career as a very well respected sports reporter in Minneapolis. He is also a big Minnesota Twins fan. In 1991 the Twins and Braves met in the World Series. One of the worst calls in the history of baseball was made when Twins’ first baseman Kent Hrbeck pulled Braves’ runner Ron Gent off of first base, then tagged him. Gant was inexplicably called out, an outrageous travesty. Howie and I have been arguing about whether Gant was safe or out ever since.

Howie was at the Twins’ game today and he arranged this:

Was Gant safe or out? You can decide.

Thank you again for this wonderful day.

With love,

Tricia

What a Long, Strange Trip It’s Been

Today is the 30th anniversary of my ordination to the priesthood. (Many of you seem to already know that, which makes me suspect that some emails were sent without my knowledge).

Thirty years is a milestone of sorts. I hope you’ll indulge me for not preaching on the Biblical texts today, but instead reflecting on the path that has led me to this place.

For the past four years I have been the chair of the diocesan Commission on Ministry. In the Episcopal Church we believe that discernment is done in community. You don’t have a dream one night that God is calling you to ministry, then get immediately ordained.

Our process is much more structured and involved than that. It culminates in coming before the Commission on Ministry, made up of lay and clergy members, who have the sacred responsibility of discerning God’s call to the people who come before us, and who to recommend to the bishop for postulancy, the official word for those attending seminary with the goal of ordination.

Many of the people who come before us have felt a call to ministry early in their lives. That is not my story.

I was clear from an early age what my career goals were. I wanted to be a writer, and more specifically a journalist. More specifically still, the editor of The New York Times. Or maybe The Washington Post. So I headed to the University of Georgia to study journalism.

All through my childhood I attended St. Martin’s Episcopal Church, just a few miles from here. But like so many young adults, I quit going to church when I went to college.

Sunday mornings were for sleeping. What consumed my time was working on The Red and Black, the daily student newspaper, which I was the editor of my senior year.

Perhaps the first hint that my life wasn’t going to follow an ordinary path came two years after I graduated. I left my job as a reporter for The Greenville (SC) News to join the Peace Corps, going to Thailand to teach English in a rural Thai high school. Looking back now, I can say that my strong desire to be of service in the world was deeply rooted in my faith. But I wouldn’t have put it that way then.

The three years in Thailand (I stayed a third year to work for Save the Children in a refugee camp) played a strong role in my spiritual development. For most of that time I was the only foreigner and only Christian in my village. Everyone else was Buddhist, and I developed a deep respect for that faith.

The experience of being immersed for so long in such a different culture gave me a deep respect for people of other cultures and faiths. That time showed me what I already instinctively knew — that there are many different and valid paths to God.

After my time in Thailand, I returned to journalism, this time as a reporter for the Nashville Banner, where for a time my boss was my old Red and Black pal, and now St. Dunstan’s member, Bob Longino. I loved my work there as a political reporter and later an editor.

One of my colleagues at the Banner attended an inner-city Episcopal Church, St. Ann’s. He kept inviting me to attend church with him, and I kept politely declining. But I did tell him that if he ever needed someone to help when it was the church’s turn to staff a shelter for homeless families to call me.

Late one afternoon he did. That phone call changed my life.

The other volunteers at the shelter that night were all members of St. Ann’s, including its rector, Michael Moulden. We stayed up all night laughing and talking. When we were leaving the next morning, Michael said, “You should come to St. Ann’s some Sunday.”

“Maybe I will,” I replied.

The next Sunday I did.

The only way I can describe that Sunday is that as soon as I walked in the door at St. Ann’s I felt I had found a home that I hadn’t even known I was searching for. Michael preached about staying at the shelter, naming the people from St. Ann’s who had been there. He included me. I went up to receive communion and he called me by name as he put the bread in my hand.

The next Sunday, and every Sunday thereafter, I was back. St. Ann’s at that time was a small, struggling parish on the wrong side of the Cumberland River. The congregation was a hodgepodge of humanity — residents of the nearby housing project, blue collar workers, Vanderbilt doctors and lawyers, gays and straights, Blacks and whites.

What they all shared was a deep belief that the kingdom of God is open to all people, that questioning and doubt are essential elements of faith, and that compassion and inclusiveness are the cornerstones of a Christian life.

In today’s terms it was at St. Ann’s that I realized that diversity, equity, and inclusion are essential characteristics of the kingdom of God.

Michael had a special knack for knowing how to fit people into parish life. He soon had me in an intensive Bible study and involved in outreach. After a year, much to my shock, I was elected to the vestry. A few years later, when Michael announced he had accepted a call to another parish, I was asked to be chair of the search committee for a new rector.

That job became a turning point in my life. As we spent time reflecting on what qualities we wanted in a priest, and traveling around the country interviewing candidates, I began to imagine what it might be like to be ordained. I dismissed those thoughts as “journalistic technique” — putting myself in the shoes of the person I was interviewing.

But long after we had called Lisa Hunt to be the first woman rector in the Diocese of Tennessee the thoughts persisted. Others began asking me if I had ever considered going to seminary. I would dismiss them with a laugh.

Me? A priest? Come on, that’s ridiculous.

But in truth, more and more of my passion and energy were with the church, not with the job I had once loved so much. One day a friend who had worked at the paper asked me to lunch. I confessed to him that I was becoming less and less satisfied at work, and that maybe it was time to move on to other challenges at another paper.

“I think before you do that, you need to decide what you are going to do about the church,” he said. And before I could put up my usual protests, he told me that it was obvious to all my friends that I needed to at least seriously consider going to seminary.

After that conversation, I went to see Lisa, my priest. With her guidance, I began the discernment process that ultimately led me to seminary and ordination.

I entered seminary at Sewanee looking forward to being challenged and exposed to new ideas. I was surprised to find that many of my classmates did not feel the same way.

What I saw as challenging and exciting, they saw as threatening. I was surprised to discover deep feelings of homophobia among some classmates, and even more shocked to discover that for some the ordination of women was still an issue. Still, I made lifelong friends and enjoyed the stimulation of both intellect and faith, which I believe go together.

The most influential person in my seminary education was my ethics and moral theology professor, Joe Monti.

On my second or third day at Sewanee, before I had even had Joe’s class, he called me into his office. Seminarians who received financial aid, which was most of us, were required to do work study jobs for eight hours a week.

I was assigned to work in the dean’s office, but Joe told me that day he had requested that I work for him, instead.

“I’m writing a book, and have several articles I’ve finished,” he said. “I need someone who can edit them.”

“Okay,” I replied.

“You need to understand,” he said. “I need someone who can really go through these things and edit them.”

“Okay,” I said again.

When he repeated it the third time, I asked if he knew what I had been doing until the previous week. He didn’t. When I told him I had been a newspaper reporter and editor, he said, “Oh, well, I guess you can do this.”

If he didn’t know that, I said, then why had he asked for me.

“Your GRE scores show that you’re highly verbal,” he replied.

After seminary I was ordained a deacon back at St. Ann’s, then moved to Knoxville to work at Church of the Ascension, the largest church in the Diocese of East Tennessee.

I was only there for a year, but it was an important time. The interim rector who hired me, Anne Bonnyman, is one of the finest priests I know. She and the people of Ascension gave me the gift of a good beginning to my ordained life.

It was at Church of the Ascension, on the feast of the Ascension, that I was ordained a priest 30 years ago today. Anne, who 13 years earlier had been ordained there, also on the feast of the Ascension, was the preacher. We remain close friends. I’m sure we’ll talk sometime today.

Earlier that year my friendship with Joe had evolved into something more. He lived in Chattanooga and commuted to Sewanee, an hour away. When a position at St. Timothy’s on Signal Mountain, a suburb of Chattanooga, became open, I applied and was hired.

Again, it was a fortunate move. It was there that I really learned how to be a priest. David Hackett, the rector, was a good priest, an excellent mentor, and a good friend. The parish was welcoming and accepting of their first female priest.

It was at St. Timothy’s that Joe and I were married at the 11:15 service the Sunday after Christmas. The congregation rejoiced with us again a few years later when Joseph Henry arrived in our lives. My memories of that time are overwhelmingly positive.

Then one day I received a phone call from my friend Maggie Harney. Maggie and I had gotten to know each other from annual gatherings of women clergy from around the Southeast, sponsored by Mary and Martha’s Place, which was housed at St. Dunstan’s.

Maggie told me that Margaret Rose, the rector, was leaving. She thought it might be a good fit for me.

And so, 20-plus years later, here we are, celebrating the 30th anniversary of my ordination. A little more than two-thirds of those years have been here with you. After all these years, I cannot imagine a better place to be.

It is the great privilege of my life to be here with you. To share in the sacred moments of your lives — weddings, babies, baptisms, new jobs, new loves, new joy. And to be there for the sacred hard moments — unexpected challenges and difficulties, illnesses and deaths. It is all holy ground, and it is a privilege to be invited to walk it with you.

And you have been there for us. You helped raise Joseph Henry, who was three when we moved here and celebrated his 24th birthday last week.

In the past few years you have been with me for my life’s hardest moments, especially for the long weeks of Joe’s illness and death. You prayed for us, loved us, and stood with us through it all. God was present to us through you.

There is a Facebook page that I’m part of for Episcopal women clergy. Often there are discussions about clergy’s relationships with their parishioners. Inevitably, many will say that of course they are not friends with their parishioners. That would be totally inappropriate.

And I wonder — how do they do that? What kind of community is present in their congregations?

I know about appropriate boundaries, and the different roles we have as priest and parishioners. I was hesistant about the appropriateness of talking about myself today, I consulted with Deborah Silver, who said it was okay. But this is my community. You are my friends.

In those difficult early weeks and months after Joe’s death, when I would often wake up enveloped in grief and wonder how in the world I was going to make it through the day, especially if it was Sunday, my heart would lift when I pulled into St. Dunstan’s parking lot.

It always does. Every day.

So I guess I won’t ever be the editor of The Times or The Post. That’s okay. It’s not the path I planned, but it has been a far more interesting and fulfilling one.

To borrow a line from the Grateful Dead, what a long, strange trip it’s been.

I am grateful for every bit of it.

Amen.